|

|||

|

http://aeinstein.org Le idee di Gene Sharp irrompono nella realtà

Per tutta la sua vita Gene Sharp ha studiato le strade per lottare effettivamente senza violenza. Oggi, a 83 anni, viene considerato la mente dietro alla primavera araba, e la gente prende sul serio le sue strategie. Spencer: sono passati otto anni dall’ultima intervista che le feci per Peace Magazine, e anche da quando la gente in giro per il mondo aha iniziato a darle ascolto. Sharp: Si, sono appena stato invitato da un giornale di Washington, Foreign Policy, che pubblicherà qualcosa sulle persone che hanno goduto di stima e riscontri nel mondo, durante l’ultimo anno. Quel tipo di invito non sarebbe mai arrivato solo qualche anno fa. Spencer: Lo so. Infatti possiamo cominciare dal rivedere i cambiamenti avvenuti nel suo pensiero. Se ricordo bene, lei ha cominciato come studente laureato in sociologia per poi diventare Gene Sharp, l’uomo in prima pagina sul New York Times. Cominciamo da quel tempo in cui ha iniziato a realizzare che la nonviolenza era una pratica speciale che poteva essere sviluppata attraverso utili procedure. Sharp: Ah si! Una cosa che era nella mia tesi era la tipologia della nonviolenza. Avevo classificato sei o sette sistemi di fede, di cui uno era chiamato la “resistenza nonviolenta”. Quella era una categoria diversa ma era elencata assieme alle altre. (Oggi non mi piace più il termine nonviolenza, ad eccezione di usi molto speciali) Quella tipologia è passata attraverso diverse revisioni e una di queste fu pubblicata sul Journal of Conflict Resolution, che era una nuovissima pubblicazione all’epoca. In quella pubblicazione trattai la lotta nonviolenta come una categoria separata. Rappresentava una rottura nel mio pensiero, perché la gente non aveva più bisogno di una fede per agire. Ricordo una volta nel seminterrato della biblioteca dell’Università Statale dell’Ohio. Stavo leggendo vecchi quotidiani dell’India sul conflitto, credo fosse la campagna del 1930, e la prova era là: questa gente non crede nella nonviolenza come etica! Fu uno shock. On avevamo fotocopiatrici allora, dovevo copiare l’intero articolo a mano e pensai: dovrei copiarlo? Non dovrebbe essere così. Alla fine il mio interesse per la realtà l’ebbe vinta e fortunatamente lo copiai. Più tardi realizzai che non era un problema, ma una novità un apertura! La gente non deve credere in una fede per praticare questa forma di azione! Quindi era aperta a tutti. Quel punto di rottura fu nel 1950 o 51. Spencer: quindi il risultato fu che la gente può praticare la lotta nonviolenta senza essere eticamente impegnati con la nonviolenza. Sharp: Si. Spencer: quest’affermazione sembra controversa. Molti attivisti e pacifisti pensano che devi iniziare purificando il tuo cuore, la tua mente e la tua anima, e solo dopo puoi agire la nonviolenza. Sharp: Uh huh: altrimenti dovrai usare la violenza. Questa è l’implicazione. Spencer: ridendo, entro in argomento con alcuni pacifisti con qualche versione di quell’idea. Sharp: ho perso la pazienza con alcuni di costoro. Ho scritto una lettera, alcuni anni fa, per il Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute sulla responsabilità di chi crede nell’etica della nonviolenza, di esplorare anche lo stesso tema in modo pragmatico. Non ho mai avuto risposta alcuna. Non fu mai pubblicata. A quel tempo nella Biblioteca, anch’io mi sentivo minacciato da quel pezzo di informazione. Era pura eresia! (vedi Principled and Pragmatic Peace per focalizzare l’argomento) Spencer: Ma il suo è un pensiero di rottura perché la gente inizia a praticarlo. Sharp: Non rivendico la paternità di quella rottura. La gente ha compreso molto prima di me. In particolare Bart de Light in Olanda. Ehli scrisse un importante libro intitolato Conquest of Violence: An Essay in War and Revolution. Nel libro egli non lo dice esplicitamente ma scrive sulla base di quell’assunto attraverso tutta la sua analisi. Un altro libro fu The Power of Nonviolence di Richard Gregg, dove vengono descritti dodici esempi di azione nonviolenta nella storia. Egli presuppone che la nonviolenza sia legata alla conversione. Ci furono altri libri sugli scioperi dei lavoratori e il boicottaggio economico. Quei libri furono molto importanti. Non li avevo nel 1949 ma li anntai a pie di pagina nel mio libro The Politics of Nonviolent Action, nei capitoli che hanno a che fare con i metodi. Spencer: Ha detto che non ama usare la parola nonviolenza, non le ho mai sentito dire questa affermazione prima d’ora. Sharp: Potrebbe essere utile in qualche caso come ad esempio; la folla nella piazza si mantenne nonviolenta, oppure; queste persone credono nella nonviolenza come etica. Ma usare quella parola in una situazione rivoluzionaria dove la gente sarebbe felice di usare violenza se ne avesse i mezzi, non sarebbe la stessa cosa. Ha il mio dizionario? Spencer: no Sharp: Oh, è uscito il due di novembre. Ci ho lavorato per decenni. E’ veramente eretico che sia pubblicato da quell’editore rivoluzionario che è la Oxford University Press. Ci sono 997 voci e 847 definizioni. Spencer: se è così grande avrà illustrato le voci con casi storici? Sharp: No, è nel secondo volume di The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Ci sono solo pochi casi dove l’ho fatto in quel libro. Tuttavia, Oxford mi chiese di scrivere un saggio sul potere politico, cosa che feci, e allora mi dissero che avrebbero voluto che tenessi conto dei tipi di lotta che venivano usati, così usai le descrizioni di Joshua Paulson in Serbia, che era in Waging Nonviolent Struggle, e Jamila Raqib scrisse una descrizione delle azioni recenti in Tunisia. Queste furono aggiunte al dizionario. La copertina è gialla sgargiante con un pugno. Spencer: Il pugno di Otpor. Lei ha dei seguaci che portano il suo messaggio su se stessi. Per esepio, la gente di Otpor in Serbia ha un’organizzazione chiamata Canvas, che sembra praticare ciò che la Albert Einstein Institution ha sempre promosso. Sharp: In linea di massima penso che sia corretto. Srdja Popovic mi ha fatto visita un paio di mesi fa, quando era negli Stati Uniti. E’ un ragazzo eccellente. Altri che hanno lavorato con me sono cresciuti con le loro prospettive e le loro ambizioni, non sono mica burattini! Spencer: Ci sono altri gruppi simili a Canvas che implementano le sue idee? Sharp: Forse. Nuovi gruppi usano sempre From Dictatorship to Democracy, e a volte chiedono il permesso di tradurlo. Jamila da loro rigide istruzioni su come tradurre e cosa non fare. Ci sono diverse traduzioni in lingua indigena in Africa. Questa è una delle ragioni per cui il nuovo dizionario sarà molto utile. Spencer: Ci sono divisioni o fazioni incompatibili tra coloro che studiano il suo lavoro? Sharp: non la metterei così, ma ci sono variazioni tra costoro in termini di obiettivi. Spencer: Parliamo della Primavera Araba. Di recente le sue idee sembrano aver ispirato intere popolazioni dal Medio Oriente al nord Africa. Cosa che ha reso il suo nome più autorevole di quanto non fosse durante il movimento contro Milosevic o durante la rivoluzione colorata in Ukraina, Georgia e così via. Lei è considerato il cervello dietro la Primavera Araba. Sharp: Ne ho sentito parlare, ma non colgo l’evidenza. Un attivista egiziano a cui fu chiesto di me, negò fermamente l’assioma. Poi, di recente, ebbe a dire che forse era proprio così. Non so. Sono restio ad accettare crediti per cose che altre persone hanno fatto. Se le mie idee sono state utili a dimostrare ciò che è possibile, ne sono felice, ma non mi metto l’aureola per questo. Spencer: Dopo l’inizio del movimento egiziano, ci fu un contagio con altri movimenti nel mondo arabo. Mi sembra che questa gente abbia solo reagito a quello che hanno visto sui media, senza però aver pianificato alcuna strategia. Ho pensato che non avrebbero avuto successo o che non sarebbero rimasti nonviolenti. Una parte di me stessa si rallegrava mentre l’altra si preoccupava per loro. E infatti, abbiamo visto cosa è successo in Libya, Yemen, Bahrein e Syria, le cui rivolte sono divenute improvvisamente difficili e pericolose. Se avesse potuto avvisarli mentre la Pimavera Araba era solo agli inizi, durante i primi tempi della azioni al Cairo, quali suggerimenti avrebbe voluto offrire ai popoli che volevano emulare i tunisini e gli egiziani? Sharp: primo, avrei iniziato qualche anno prima. Era un pò tardi iniziare lì per lì ad immaginare che cosa si sarebbe dovuto fare. Ci sono state persone che sono venute da noi da alcuni paesi del Medio Oriente, in particolare dalla Syria, ma io mi sono rifiutato di dire loro cosa fare. Non conosco la loro situazione e i miei consigli avrebbero potuto essere sbagliati. Dissi loro: dovete prepararvi, dovete studiare. Circa un anno fa, abbiamo messo insieme il risultato di quella lunga corrispondenza tra noi ed alcune visite personali, e anche due o tre giorni di riunioni con il gruppo di un paese, ne abbiamo ricavato un nuovo libro: Self-Liberation. Spencer: davvero! Lei è sempre molto impegnato! Sharp: abbiamo rifiutato di dir loro cosa fare ma facciamo qualcosa oggi. Abbiamo detto loro: Pianificate la vostra strategia. Cosa dovete sapere prima di farlo? Dovete conoscere la vostra situazione e quella della vostra controparte, profondamente, come probabilmente non la conoscete ora, anche se vivete nello stesso paese. quali sono i problemi di quella società? Trovate i punti deboli del sistema a cui vi opponete. E, secondo, dovete comprendere la strategia nonviolenta nel profondo. Nessuno lo fa veramente, incluse quelle persone che sostengono i mezzi nonviolenti. Per arrivare a ciò, ci sono testi, miei in maggior parte, ma anche di Bob Helvey. Così ho selezionato 900 pagine da una massa di letture da cui trarre le basi per una comprensione approfondita della lotta nonviolenta. Quali sono le vostre esigenze per l’efficienza? E quando le hai imparate potresti non essere ancora pronto se non sei in grado di pensare strategicamente. Se non riesci a pensare strategicamente non puoi pianificare una strategia. Possiamo solo darloro indizi in quella direzione. Non possiamo dire fai queste tre cose e sarei uno stratega geniale. E’ stato tutto pubblicato, è anche sul nostro sito, comprese le 900 pagine di letture. E’ anche tradotto in cinese, con traduzioni in corso per l’arabo e il farsi. Se qualcuno pensa che non leggeranno tutte quelle pagine, allora non sono così interessati alla loro liberazione. E’ un piccolo prezzo da pagare per essere in grado di pianificare la tua liberazione. Le letture sono tratte per lamaggior parte da The Politics of Nonviolent Action, e anche da altre fonti che tu già conosci. Spencer: Voglio organizzare una conferenza qui a Toronto sulla controversa questione se sia appropriato e accettabile, per un governo, promuovere la democrazia in altri paesi. Per me è assurdo per chiunque polemizzare su questo, ma da quando George W. Bush ha iniziato ad imporre la democrazia in Iraq, la sinistra si è rivoltata contro l’idea di assistere la democrazia oltremare. Essi considerano che qualunque cosa un paese, specialmente gli USA, faccia per sostenere la democrazia sia un atto di imperialismo. Quindi vorrei portare questa discussione allo scoperto perché rimane ancora molto controversa. Sharp: Si. Abbiamo quel tipo di opposizione perché, forse quindici anni fa, abbiamo ricevuto indirettamente dei fondi National Endowment for Democracy. Era dal National Democratic o dal National Republic Institute, che indirettamente proviene da proprietà del Congresso. Da allora in poi siamo diventati strumenti dell’imperialismo, e non siamo credibili neppure oggi. Questo è puro dottrinarismo. Non tollero questo tipo di nonsense. Spencer: bene se il NED volesse darmi dei fondi, li prenderei. Non ho grosse obiezioni su ciò che fanno. Sharp: Dodici persone sono venute a trovarli da Mosca. E’ stato persino difficile farli entrare tutti nel nostro piccolo ufficio. Essi si aspettavano un grande spazio con molti uffici, a causa della nostra influenza. Sono rimasti shockati perché se avevamo ricevuto tanto denaro non avremmo voluto continuare a lavorare in queste ristrettezze. Spencer: Moltissimi russi sono ostili alle rivoluzioni colorate e pensano che lei sia uno dei cattivi. Sharp: Uh huh. La storia russa ignora totalmente la lotta nonviolenta. Spencer: Infatti. Che mi dice dell’Iran? Ho avuto molte speranze che la loro Rivoluzione Verde ce la facesse. Come mai non sono riusciti? Qualche dissidente iraniano è venuto da lei per dei consigli? Sharp: se l’avessero fatto non li avremmo consigliati. Avremmo dovuto sapere di che tipo di consigli avessero bisogno. Spencer: ride, ma come? Lei ha una storia di aiuto ai gruppi, di analisi delle loro risorse e di quelle del regime. Non è come se lei non avesse mai aiutato nessuno. Sharp: possiamo essere d’aiuto in generale. Guarda qui! Esamina questo! Non dimenticare di fare questo! Questo è il tipo di cose che facciamo ed è tutto nella guida alla Self-Liberation. Libro che aiuta la gente ad essere in grado di pianificare la propria strategia. Spencer: Questo libro, Self-Liberation, è un aggiornamento di From Dictatorship to Democracy? Sharp: No. From Dictatorship to Democracy offre un ampio quadro concettuale del pensiero di come sbarazzarsi dei dittatori. Spencer: Allora Self Liberation è più specifico? Sharp: Si, e quando ogni gruppo se ne impadronisce, lo fa proprio, diventa più specifico rispetto ad ogni paese in particolare, in ogni particolare periodo di tempo. Spencer: Mi dica ilsuo pensiero sulla Libia. Sharp: Non so molto della situazione libyca, ma ho imparato alcune cose da, per esempio, un corrispondente della Reuters che era qui. Moltissime persone pensano che il passaggio alla violenza sia avvenuto perché il regime di Gheddafi o le sue inacce di future violenze erano così dure che i mezzi nonviolenti non avrebbero potuto confrontarsi. Ma ciò che accadde veramente è diverso. Ci fu un generale che disertò le forze governative, portando con se le proprie truppe e le loro armi, offrendo ai suoi soldati la rivolta. E loro accettarono. Ma perche disertò? Questo stesso generale fu ucciso più tardi bel campo dei ribelli. Perché un generale disertore per la rivoluzione viene ucciso nel campo dei rivoluzionari? E perché due settimane più tardi Gheddafi e suo figlio hanno svoltato con la violenza predicendo la guerra civile? Nonostante non sia documentato, io penso che quel generale era un agente provocatore che offriva ai ribelli qualcosa che non potevano rifiutare. Poi chiesero l’aiuto internazionale. E fu fatta. Spencer:Interessante. Non ricordo i metodi che i ribelli usarono in quella fase, ma erano nonviolenti. Ghedafi disse: andrò porta a porta ed ucciderò questa gente come topi. E la gente pensò che fosse necessario fare qualcosa per proteggere molte migliaia di persone in Benghazi. Se lei fosse stato con oro in quel momento pensa che sarebbe stato possibile fare qualcosa per aiutarli a vincere? C’era una via, in quel momento, per lottare senza accettare le armi che l’agente provocatore gli aveva messo in mano? Sharp: Penso di si, ma non ho sufficienti informazioni sulle condizioni esistenti in quel momento. Si presuppone che se le cose si fanno difficili, bisogna passare alla violenza. troviamo nella storia della nonviolenza che anche in situazioni estreme quando non sarebbe possibile il confronto, i metodi nonviolenti funzionano comunque. Ma poi, l’intervento militare salva le vite? No. Ho visto dei grafici sulle percentuali delle vittime e dei morti dopo il passaggio alla violenza, e sono assolutamente orrendi.l’intervento militare non fa nulla per salvare le vite. Ha l’effetto opposto. Guerra, ribellioni violente, guerriglia hanno una percentuale di vittime immensa. I metodi militari per salvare le vite non funzionano affatto. Spencer: Cosa sarebbe successo se Gheddafi e il suo esercito avessero attaccato Benghazi con l’intento di ripulirla dai ribelli? Se fosse successo come in Ruanda o in altri terribili casi. Ho degli amici esperti di strategie militari che dicono che sarebbe stato impossibile, ma diciamo che una forza armata di peacekeeping fosse entrata in libya e si fosse interposta tra i due contendenti, e avesse detto: adesso nessuno è autorizzato a sparare dall’altra parte. Siamo pronti a prevenire ogni aggressione contro entrambe le parti. Non siamo qui per prender parte ad una guerra civile. Ma siamo qui per impedirla. Quindi indiciamo un cessate il fuoco e iniziamo a negoziare. Questo tipo di intervento avrebbe salvato le vite? Ammettendo, come dicono i militari, che fosse impossibile: Sharp: non posso farmi coinvolgere in questo tipo di finzione politica. E’ troppo ipotetica. Sulla base di un ipotesi lei propone una particolare azione militare che non è affatto ipotetica. E’ molto concreta e sappiamo quali sono le conseguenze di un intervento militare. Guarda, chi è adesso a controllare il governo libico? Spencer: Probabilmente i leader islamici.uno di loro ha già proposto di ritornare alla Sharia, quando un uomo poteva avere molte mogli. Non molte donne occidentali sarebbero state contente di sostenere quel tipo di cambiamento: Sharp: No, ma sono le pressioni USA e le influenze Occidentali che controllano le cose. Non certo gli islamici. Spencer: Lo pensa davvero? E ride. Bene non saprei cosa scegliere tra le due possibilità. Penso che il lavoro per costruire la democrazia cominci solo ora. Una volta che il conflitto è terminato, sorgono molti nuovi problemi da risolvere per creare la democrazia. Specialmente in Syria, così frammentata da conflitti etnici e religiosi, non sarà facile. Sharp: No, non lo sarà. Anche là, ancora alcuni ufficiali dell’esercito syriano hanno disertato il regime. Poi hanno pensato che ritirarsi dall’esercito non era abbastanza, ma che avrebbero dovuto combattere l’esercito syriano, che non erano in grado di sopraffare senza una grande guerra civile, con un numero tremendo di vittime e senza alcuna prospettiva realistica. Non ci sarebbe stata alcuna soluzione nonviolenta. C’è una guerra civile ed è molto brutta. Spencer: alcuni anni fa ero molto vicina ad alcune persone Karen dalla Birmania. Essi credevano che, anche se ci fosse stato un accordo e la giunta avesse fatto un passo indietro e girato il potere al partito di Aung San Suu Kyi, dopo le elezioni, ci sarebbero stati ugualmente problemi a causa del lunghissimo conflitto tra i vari gruppi etnici. Ce ne sono almeno undici in Birmania. Essi credevano che la via migliore per aiutarli fosse organizzare conferenze preparatorie alla democratizzazione qui a Toronto, come un modo per anticipare il tempo in cui sarebbero stati in grado di formare un nuovo governo, lavorando da subito alla risoluzione dei vecchi problemi etnici. Essi pensavano che questo avrebbe migliorato le loro prospettive di creare una vera e funzionante democrazia quando sarebbe venuto il momento. Lei crede che questo approccio sia utile anche ad altri paese nella situazione della Birmania? Sharp: Se fosse successo, non credo che avrebbe fatto del male, ma non credo neppure che avrebbe fatto alcun bene. E’ un’idea romanticaa. Si prende qualcosa che è vecchio di decenni. Le sue radici sono profonde. Non c’è nulla che si possa risolvere portando genti ad incontrarsi in luoghi diversi dalla norma. Spencer: Bene, è quello che abbiamo appena detto della Syria, diciamo che Bashar al Assad faccia un passo indietro oggi (cosa che forse dovrà fare prima che andiamo in stampa) e che lasci tutto nelle mani dell’opposizione. Formare una nuova democrazia sarebbe molto difficile. Non pensa che si dovrebbe comunque anticipare i problemi e lavorarci sopra prima del tempo? Sharp: Non è abbastanza parlarne. Non so che cosa succederà. Spencer: Ma lei ha il presentimento che ci sarà una guerra civile in Syria. Sharp: Si. Quando c’è un esercito che decide di combattere contro l’esercito del regime, come altro può chiamarla se non guerra civile? Spencer: questo è un pensiero triste con cui chiudere la nostra conversazione. Non avrebbe un pensiero più felice da condividere? Sharp: Per decenni ci sono state persone che erano interessate al tipo di lavoro che stavo facendo. Quando ci sentivamo scoraggiati ero solito dire: ci sarà un punto di rottura quando la gente prenderà sul serio tutto questo. Ma quel momento non venne un anno dopo l’altro. Dieci anni passarono e poi altri dieci ma il momento non veniva. Penso che il punto di svolta sia ora. Oggi queste cose vengono prese seriamente. Puoi prendere una pagina del New York Times. Proprio questa settimana ho letto sul London Sunday Times il tremendo responso dopo la Tunisia e l’Egitto. Siamo sommersi dai giornalisti. I giornalisti non hanno mai prestato attenzione ai miei scritti. Hanno sempre nutrito falsi preconcetti, malintesi. Ma in questo tempo, iniziato nelle sei settimane tra marzo e aprile, siamo stati sommersi dai reporters da tuttoil mondo. Giornali asiatici e sudafricani, per esempio. Avevamo tra le quattro e le sette interviste al giorno, per almeno sei settimane, ma nessuno di quei giornalisti veniva con quei vecchi preconcetti e malintesi. Nessuno! Tutti comprendevano le realtà basilari. E gli editori che affidavano loro gli incarichi pensavano che i lettori sarebbero stati interessati a leggerne.tutto questo è assolutamente nuovo e dobbiamo iniziare a pensare diversamente. Come ci confronteremo con questa situazione d’ora in poi?

http://peacemagazine.org

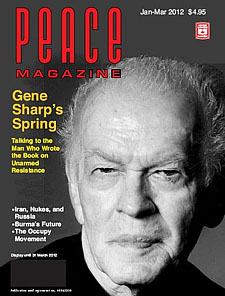

Gene Sharp's Ideas are Breaking Through

All his life Sharp has studied ways of fighting effectively without violence. Now that he is regarded, at 83, as the brains behind the Arab Spring, people are taking his strategies seriously. METTA SPENCER: It has been eight years since I last interviewed you for the magazine. Since then people around the world have begun to listen to you. SHARP: Yes, I was just now invited to a Washington journal— Foreign Policy —who will publish something about people who had some response in the world in the last year. That kind of invitation never happened a few years ago. SPENCER: I know. In fact, let’s begin by reviewing the changes in your own thinking. As I recall, you started off as a graduate student in sociology working on a masters thesis and have managed to turn into Gene Sharp, the guy on the front page of the New York Times. Let’s start at the time when you began to realize that nonviolence was a special set of practices that could be developed into useful procedures. SHARP: Ah yes! One thing that was in the masters thesis was a typology of nonviolence. I classified six or seven belief systems, of which one was called “nonviolent resistance.” That’s a different category but it was in with the others. (Today I don’t even like the term “nonviolence” except for very special uses.) That typology went through several revisions and one was published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, which was an entirely new publication at the time. In it I took out nonviolent struggle as a separate category. That was a breakthrough in my thinking—that people didn’t have to have the belief in order for them to act. I remember one time in the basement of the Ohio State University library. I was looking through old Indian newspapers on the conflict—I think it was the 1930 campaign—and the evidence was there: These people did not believe in nonviolence as an ethic! That was a shock. I thought: Oh dear! We didn’t have copy machines then. I had to copy the whole thing by hand and I thought; Should I copy that down? It’s not supposed to be that way. But my focus on reality won out, fortunately, and I copied it down. Later I realized that it wasn’t a problem. It was a breakthrough, an opening! People didn’t have to believe in order to use this form of action! Therefore, it was open to almost everybody. That breakthrough was in about 1950 or ’51. SPENCER: So it was the fact that people could do nonviolent resistance without being ethically committed to nonviolence. SHARP: Yes. SPENCER: That’s still controversial. A lot of peace activists believe that you have to start by purifying your heart and mind and soul—and then you might be entitled to use nonviolence. SHARP: Uh huh. Otherwise, you’ve got to use violence. That’s the implication. SPENCER: (Laughs.) I still get into arguments with people about some version of that issue. SHARP: I’ve lost my patience with some of these people. I did a paper for Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute a few years ago on the responsibility of people who believe in it as an ethic to also explore it pragmatically. I never got any feedback on that at all. It was never published (See Principled and Pragmatic Peace in this issue for a précis, discussion, and link). At that time in the library, I too felt quite threatened by that piece of information. That was heresy. SPENCER: But your thinking is a breakthrough because people are beginning to look at it. SHARP: I don’t claim credit for that breakthrough. People were coming up with that long before me. Particularly Bart de Ligt in the Netherlands. He had an important book called Conquest of Violence: An Essay in War and Revolution. In it he didn’t say that but he was operating on that assumption throughout the whole analysis. Another one was The Power of Nonviolence by Richard Gregg, who described twelve examples of nonviolent action from history. He operated on the assumption that it was tied together with conversion. There were other books on labor strikes and economic boycotts. Those books were extremely important. I didn’t have them in 1949 but they were footnoted in my book, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, in the chapters dealing with those methods. SPENCER: You said you no longer like to use the word “nonviolence.” I never heard you say that before. SHARP: It can be useful for some things, like “the crowds in the square maintained nonviolence,” or “these people believe in nonviolence as an ethic.” But to use that same word for people in a revolutionary situation who would be very happy to use violence if they had the means, but they didn’t-to lump those all together as the same thing? Have you got my dictionary? SPENCER: No. SHARP: Oh, my goodness. It came out on November 2. I worked on it for decades. It’s so heretical that it’s published by that revolutionary publication, Oxford University Press. It has 997 entries and 845 defined terms. SPENCER: If it’s that big, you must be illustrating terms with historical cases. SHARP: No, that’s in volume two of The Politics. There are only a few cases where I do that in this book. Anyway, Oxford asked me to write an essay on political power, which I did, and then they said they should have accounts of this kind of struggle being used, so I used Joshua Paulson’s account of Serbia, which was in Waging Nonviolent Struggle, and Jamila Raqib here wrote an account of recent actions in Tunisia. They were added to the dictionary. The cover is bright yellow with a fist. SPENCER: The Otpor fist. You have followers who are carrying your message on their own. For example, the Otpor people in Serbia have an organization now called CANVAS, which seems to be doing what the Albert Einstein Institution has always favored. SHARP: Broadly, I think that’s accurate. Srdja Popovic visited here a couple of months ago when he was in the US. He’s a bright guy. Other people who work with me wind up with their own perspectives and their own career ambitions. They’re not puppets! SPENCER: Are there other groups similar to CANVAS that are implementing your ideas? SHARP: Maybe. Groups often use From Dictatorship to Democracy, and sometimes they ask our permission to translate it. Jamila gives them strict instructions on how to translate it and what not to do. There are several translations into indigenous languages in Africa. That’s one reason the new dictionary will be helpful. SPENCER: Are there incompatible splits or factions among people who carry on your work? SHARP: I wouldn’t put it that strongly, but there are variations among them in terms of objectives. SPENCER: Let’s talk about the Arab Spring. Recently your ideas seem to have inspired people throughout the Middle East and North Africa. That has made your name more prominent than it was during the movement against Milosevic or the color revolutions in Ukraine, Georgia, and so on. You’re called the brains behind the Arab Spring. SHARP: I hear that but I don’t see the evidence. One Egyptian activist who was asked about it denied that it’s the case at all. But he had earlier said that it was the case. I don’t know. I resist people giving me the credit for what other people have done. If my ideas have helped show what’s possible, I’m happy for that, but I don’t use that to advance my halo. SPENCER: After the Egyptian movement began, there was a contagion of movements throughout the Arab world. I worried that these people were just reacting to what they had seen in the media, but had neither planned nor strategized. I thought they were unlikely to succeed or to remain nonviolent. Half of me was rejoicing that they were doing this, but the other half was worried for them. And indeed we saw that Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, and Syria quickly became very difficult and dangerous. If you were giving advice then, when the Arab Spring was just budding during the Cairo actions, what suggestions would you have offered to the people who wanted to emulate the Tunisians and the Egyptians? SHARP: Number one, I would have started a few years earlier. It was a bit late in the game to start figuring out what you’re going to do. We did have people coming to us from certain Middle Eastern countries, particularly Syria, and I refused to tell them what to do. I don’t know their situation and my advice might be erroneous. I said: You need to prepare, you need to study. About a year ago we pulled together the results of that lengthy correspondence between us and some personal visits, and a two-day or three-day session with a group from one country, into a new book: Self-Liberation. SPENCER: Really! You are one busy man! SHARP: We refuse to tell them what to do but we do know something. We tell them: Plan your own strategy. So what do you need to know before you do that? You have to know your own situation and your opponent’s in great depth—which you probably don’t know now, even though you live in the country. What are the problems of that society? Find the weaknesses of your opponent’s system. And, number two, you’ve got to understand nonviolent strategy in depth. And nobody usually does, including the people who are advocating the nonviolent means. To get that, there are writings-mostly my own, and some from Bob Helvey. So I selected 900 pages from massive amounts of readings to get the basic understanding of nonviolent struggle. What are its requirements for effectiveness? And when you get those, you’re still not ready if you can’t think strategically. You have to be able to think strategically or you can’t plan a strategy. We can only give them clues in that direction. We can’t say: Do these three things and you’ll be a strategic genius. That’s published. It’s also on our web site, with all the 900 pages of readings. And it’s already in Chinese, with translations pending in Arabic and Farsi. If somebody says they’re not going to do that much reading, then they’re not interested in their liberation. It’s a small price to pay for the ability to plan your liberation. The readings are mainly from The Politics of Nonviolent Action, and other sources that you probably have already. SPENCER: I want to put on a conference here in Toronto about the controversy as to whether it is appropriate and acceptable for one government to promote democracy in other countries. To me it’s absurd for anyone even to question that, but since George W. Bush began to “impose” democracy on Iraq, the left has turned against the very idea of assisting democracy overseas. They consider anything that a country (especially the US) does to support democracy would be an act of imperialism. I want to bring that discussion back into the open because it remains so controversial. SHARP: Yes. We get that kind of opposition because, maybe fifteen years ago, we got some money indirectly from the National Endowment for Democracy. It was from the National Democratic or the National Republic Institute, which indirectly came from a US Congress appropriation. Therefore we were tools of imperialism some years ago and shouldn’t be trusted today. That’s pure doctrinalism. I have no tolerance for such nonsense. SPENCER: Well, if NED wanted to give me some money, I’d take it. I don’t have many objections against what they do. SHARP: Twelve people came here from Moscow. We could hardly get all of them into our tiny office. They were expecting a big suite of offices because of us having so much influence. They were in shock because if we were getting so much money we wouldn’t be working in these restricted circumstances. SPENCER: A lot of Russians are hostile to color revolutions and think you’re one of the bad guys. SHARP: Uh huh. Totally ignoring the nonviolent struggles in Russian history. SPENCER: Indeed. What about Iran? I had so much hope that their Green Revolution was going to make it. Why has that not paid off? Have any Iranian dissidents come to you for advice? SHARP: If so, we don’t give them advice. We’d have to know what advice they need. SPENCER: (Laughs) Come on! You do have a history of helping groups analyze their own resources and the resources of the regime. It isn’t as if you’ve never been helpful. SHARP: We can be helpful in general terms. Look at this! Examine that! Don’t forget to do this! That’s the kind of thing we do and it’s in the Self-Liberation guide. It helps people become competent to plan their own strategy. SPENCER: Is this Self Liberation an updating of From Dictatorship to Democracy? SHARP: No. From Dictatorship is a broad conceptual framework of thinking about how to get rid of dictators. SPENCER: So Self Liberation is more specific? SHARP: Yes, and as each group takes hold of that, it’s going to become more specific about each particular country, each particular period of time. SPENCER: Tell me your thinking about Libya. SHARP: I don’t know much about that situation but I’ve learned some things from, for example, one Reuters correspondent who was here. Lots of people think that the shift to violence occurred because the Ghadafi regime or its threats of future violence were so harsh that nonviolent means couldn’t deal with it. But what actually happened was different. There was a general who defected from Ghadafi’s forces, bringing his troops and his weapons with him, and offered them to the rebels. And the rebels accepted that. But why did he defect? This same general was killed later on in the rebels’ camp. Why would a general defecting to the revolution be killed in the revolution’s camp? And why is it that Gadhafi and his son, two weeks before the shift to violence, predicted that it would become a civil war? Although unsupported by documentation, I believe that this guy was a high-level agent provocateur trying to offer the rebels something they couldn’t refuse. Then they asked for international help. It was a set-up. SPENCER: Interesting. I can’t recall the methods that the rebels were using at that phase, but they were nonviolent. Gadhafi said “I’m going to go door to door, killing these people like rats,” and people believed it was necessary to do something to protect many thousands of people in Benghazi. If you had been with them at that point, do you think it would have been possible for them to win? Was there a way for them, at that point, to have struggled on, without accepting the arms that the agent provocateur was offering them? SHARP: I think so but I don’t have detailed knowledge of the conditions at that time. There’s the assumption that if things are going to be tough, you have to go to violence. We find a history of nonviolence in extreme situations where it should not have been possible, but where nonviolent means worked anyhow. But is military intervention going to save lives? No. I’ve seen figures about the casualty rates and deaths after that shift to violence occurred, and they are absolutely horrendous. Military intervention did nothing to save lives. It had the opposite effect. War, violent rebellions, and guerrilla warfare have immense casualty rates. So the faith that military means are the only way to save lives-they don’t do much saving. SPENCER: What if it actually got to the point where Gadhafi and his army were approaching Benghazi with the intent to wipe everybody out? I would see that situation as likely to lead to what happened in Rwanda or other horrible cases. My friends who know about military strategy say that this was absolutely impossible, but let’s say a peacekeeping army went in, interposed itself between the two armies, and then said: “Now, nobody is allowed to shoot at the other side. We are going to prevent aggression against both sides. We’re not here to take sides in a civil war. but we’re here to prevent the war. Now let’s have a ceasefire and negotiations.” Would that have saved lives? Admittedly, according to military people, that was not possible. SHARP: I can’t engage in that kind of political fiction. It’s too hypothetical. On the basis of a hypothesis you’re going to propose a particular military action which is not hypothetical. It’s quite concrete, and we know what military interventions do. Now, look—who’s going to be controlling the new Libyan government? SPENCER: Probably the Islamist leaders. One of them has stated the intention to go back to Shari’a law, according to which a husband could have multiple wives. Not many Western women would be glad we had supported such a change. SHARP: No, it’s more like US pressures and Western influences controlling things. It may not be Islamist at all. SPENCER: You think so? (Laughs.) Well, as between the two, I’m not sure which I would choose. I just think that now the work really begins—to create democracy. Once the fighting has stopped, you have a whole set of new problems in creating democracy. Syria, especially, is so fragmented by ethnic and religious conflicts that it’s not going to be easy. SHARP: No, it’s not. There again, some Syrian military forces are defecting from the regime. Then they assume that simply withdrawing military assets from the regime is not enough—they have to stay and fight the rest of the Syrian army, which they will not be in a condition to do without a major civil war, with tremendous casualties and dubious prospects. It would not be a nonviolent solution at all. It’s a civil war there, and that’s really very bad. SPENCER: A few years ago I was close to some Karen people here from Burma. They said that if there was an immediate agreement and the junta stepped down and turn everything over to Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, as elected, there would still be trouble because of the long-lasting animosities between the various nationality groups. There are about eleven ethnic groups in Burma. They believed that the way to help them would be to hold preparatory democratization meetings here in Toronto, as a way of anticipating a time when they would be able to form a government, but work through some of the old problems between them. They thought this would improve their prospects of creating a working democracy when the time comes. Would you consider such a process worth attempting for other groups besides the Burmese? SHARP: If it happened, I suppose it wouldn’t do much harm but I don’t think it would do any good at all. It’s romantic. You’re taking something that is many decades old. Its roots are deep, That’s not something you can resolve by bringing groups together in a different location. SPENCER: Well, but as we just said about Syria—let’s say Bashar al-Assad stepped down today (which he may have to do before we go to press) and left it in the hands of the rebels. Forming a new democracy there is going to be difficult. You don’t think there is any way of anticipating the problems and working through them ahead of time? SHARP: Not just by talking. I don’t know what’s going to happen. SPENCER: But you have a foreboding that there will be a civil war in Syria. SHARP: Yes. When you’ve got one army deciding to fight the established army, what else would you call that but a civil war? SPENCER: That’s a cheerless thought on which to end our conversation. Do you have any happier thoughts to share? SHARP: For decades there have been people who were interested in the kind of work I was trying to do myself. When we got discouraged I used to say: There will come a breakthrough when people will take all this seriously. It didn’t come, year after year. Ten years went by and then another ten years and it didn’t come. I think that the breakthrough has come now. This is now taken seriously. You can get a page in the New York Times. Just this week I read a story in the London Sunday Times about the tremendous response after Tunisia and Egypt. We were deluged by journalists. Journalists had never paid much attention to my writings. They all had false preconceptions, misunderstandings. But this time, starting during a six-week period in March and April, we were deluged by reporters from all over the world. Asian papers and South African papers, for example. This time we had between four and seven interviews a day for six weeks, but this time none of those journalists came with the old preconceptions and misunderstandings. None! They all now understood the basic realities. And the editors who assigned them to the job thought the readers would want to know about this. This is all new and now we have to think differently. How do we deal with this situation from now on? Gene Sharp’s most recent publication is Sharp’s Dictionary of Power and Struggle, now available through Amazon and other online booksellers.Many of his other books are available for free download: see the Albert Einstein Institute’s website at http://aeinstein.org. The journal Foreign Policy now places him in the top ranks of 100 people who are changing the world.

|

|||

| top |