|

http://www.nytimes.com March 3, 2012

The Port Huron Statement at 50° Sam Roberts is the urban affairs correspondent for The New York Times.

They are mostly in their 70s now, those quixotic college students who drafted the Port Huron Statement at a ramshackle A.F.L.-C.I.O. education retreat northeast of Detroit in 1962. Today, their “agenda for a generation” survives most famously as a punch line from the 1998 film “The Big Lebowski” in which the stoner protagonist proclaims himself an author of “the original Port Huron Statement, not the compromised second draft” Purists like Jeff “The Dude” Lebowski might dissent, but last month the historian Michael Kazin pronounced the final draft “the most ambitious, the most specific and the most eloquent manifesto in the history of the American left.”

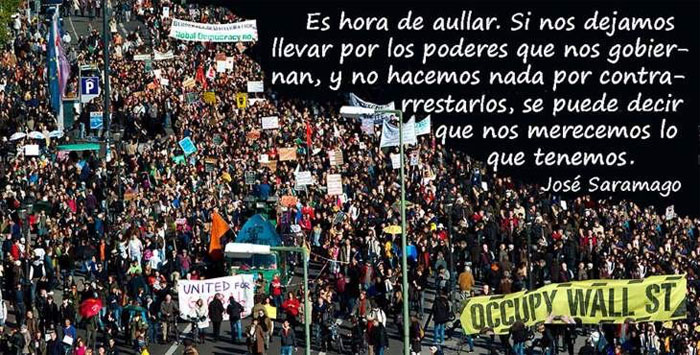

The statement that eventually emerged from a five-day national convention of the Students for a Democratic Society held June 11 to 15, 1962, contained 25,000 words. That was 7,000 more than the Communist Manifesto, which started a global revolution, and 24,300 more words than the Declaration of the Occupancy of New York City passed last September by a general assembly of the Occupy Wall Street movement, which in three weeks produced the magnitude of protests that would take S.D.S. several years to galvanize. But by invoking the spirit of John Dewey, Albert Camus, C. Wright Mills, Michael Harrington and Pope John XXIII, by at once championing and chiding organized labor as a victim of its own success (the S.D.S. began as the student arm of the League for Industrial Democracy), by elevating the university to the apex of activism and by validating liberalism and the two-party system, Tom Hayden and his colleagues forged a manifesto that still reverberates. “While most people haven’t read it, it’s still extremely relevant” for its guiding principles, said David Graeber, an anthropologist and anarchist who has been active in the Occupy movement. “For a long while I thought the Port Huron Statement was a relic of a hopeful past,” Mr. Hayden recalled last week. “But frequently students would read it and say how surprised they were at its sounding like the present.” Mr. Hayden, who was steeled by a Catholic social conscience, was 22 when he began drafting the manifesto in March 1962 in his Manhattan apartment. He was a budding journalist from the University of Michigan whose job as the principal author of the collaborative manifesto was to synthesize an inchoate angst that had been germinating in several nascent, and largely unpopular, political movements. Its guiding vision was codified by Arnold Kaufman, a philosophy professor at Michigan. He called it “participatory democracy” and, while S.D.S. would fracture, his concept would in ensuing decades be codified in school decentralization, community planning boards and freedom of information acts. At academic conferences during this anniversary year, including one recently at the University of California, Santa Barbara, scholars and grizzled activists are revisiting the document. Its last sentence was an apocalyptic downer: “If we appear to seek the unattainable, as it has been said, then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable.” Yet while American campuses were awakening from apathy, they were still several years away from radicalization. The mind-set of the Port Huron drafters — in contrast to the members of the Occupy movement — was that the fundamental values espoused by their liberal elders remained valid and that money had not yet corrupted the political system so completely that it was incapable of being reformed. That is why Mr. Hayden addressed the manifesto to the Young Left as much as to a New Left. “We would replace power rooted in possession, privilege or circumstance by power and uniqueness rooted in love, reflectiveness, reason and creativity,” the statement said. Those sentiments were echoed in Occupy’s founding principles — “constituting ourselves as autonomous political beings engaged in non-violent civil disobedience and building solidarity based on mutual respect, acceptance, and love.” “Sure, there were important things we missed,” Mr. Hayden recalled. “The environmental crisis, but Rachel Carson’s book hadn’t come out. Feminism, but Betty Friedan’s book wasn’t out. The escalation of Vietnam, which none of us expected, though we opposed. The assassination of J.F.K. and other killings to follow. The subsequent radicalization and polarization that characterized the late ’60s through Watergate.” But, he continued, “the core of the Port Huron Statement rings true, and the theme of participatory democracy is relevant today from Cairo to Occupy Wall Street to Wisconsin to student-led democracy movements.” James Miller, a professor of politics at the New School for Social Research and author of “Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago,” suggests that the very concept of consensus at all costs meant that moderates compromised and militants eventually predominated. Professor Kazin, who teaches history at Georgetown and co-edits Dissent, recalled, too, that “for the anti-war militants who flooded into S.D.S. after 1965, participatory democracy seemed too hazy and abstract both in meaning and application to guide a revolution.” In 1969, the Port Huron Statement was absent from an anthology, “The New Left Reader.” But a decade later, it was excerpted in Diane Ravitch’s “American Reader: Words That Moved a Nation.” “Sadly,” she said recently, “I find what is most dated is a sort of naïve belief that human nature itself might be transformed through appeal to idealism, and that somehow our institutions will be malleable in the face of idealism mobilized.” Paul Berman, who teaches journalism at New York University, said that the statement’s appeal to young people was natural and that neither its tone nor its prescriptions could be blamed for the later atomization of S.D.S. Could Port Huron double as a manifesto for Occupy? “This new generation, whether anarchist or simply disillusioned by stolen elections, is far more cynical about politicians and elections,” Mr. Hayden said. But Occupy has learned the lessons of S.D.S., says Todd Gitlin, a Columbia University professor and author of the forthcoming “Occupy Nation.” “The primacy of nonviolence is a reaction to the ’60s, as is don’t have hierarchal organizations and don’t have visible leaders,” said Professor Gitlin, who was president of S.D.S. from 1963-64. “For the S.D.S, the prime enemy was apathy. This movement recognizes you don’t have to preach to people that they’re alienated.” In 1962, though, fewer people were. They were still groggy from the conformist Eisenhower decade and dazzled by the Kennedy mystique, which may be why the Port Huron Statement began circumspectly: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” Kalle Lasn was 20 in 1962. Today, he is the editor of Adbusters, whose Twitter tag #OccupyWallStreet branded the movement last summer. He does not feel the Occupy movement needs to look to the Port Huron statement for guidance. “If you ask me what is the most powerful, personal and collective feeling of people in the Occupy movement, it is a feeling of gloom and doom, that they’re looking toward a black hole future,” Mr. Lasn said. “I’m not quite sure we need a manifesto to say that.” |